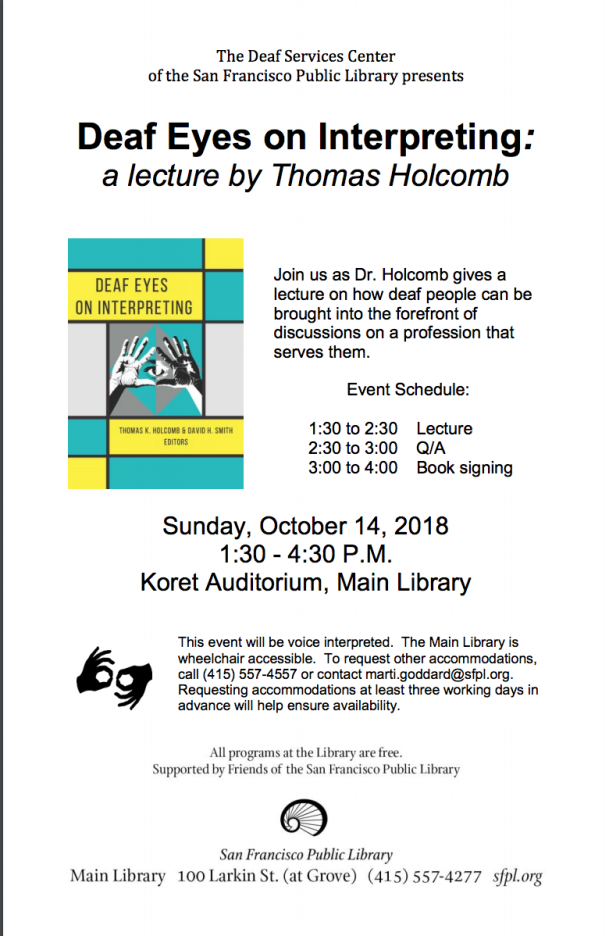

Join Tom Holcomb on Sunday, October 14th at the Main Branch of The San Francisco Public Library. He will be sharing his experiences preparing his latest book project, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting The discussion will include some of the issues that were covered in the book about ways the interpreting experience could be improved for both Deaf people and interpreters and is sure to be a lively event. See flyer below for details.

Tag Archives: interpreters

Tom Holcomb Lectures at San Francisco Main Library Sunday October 14, 1:30pm

Through the Eyes of Deaf Academics: Interpreting in the Context of Higher Education — From Deaf Eyes on Interpreting

This is the tenth installment featuring highlights from the 20 chapters in the new book, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting, edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith, which was recently released by Gallaudet University Press.

This is the tenth installment featuring highlights from the 20 chapters in the new book, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting, edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith, which was recently released by Gallaudet University Press.

Shifting the focus from the experiences of Deaf college students to Deaf professors, co-authors Dave Smith and Paul Ogden provide a close look at the expectations college faculty members have for their interpreters in order for them to successfully navigate the academic environment.

In this video clip, Dave Smith mentions several requirements for interpreting for Deaf professors in this environment where the focus is on supporting Deaf faculty members. Interpreters must possess an understanding of the wider context of higher education, including the specifics of the tenure and promotion process, the importance of collegiality, the critical need for appropriate register in voice interpretations, a feeling of trust between the professor and interpreter and even the vital role of the interpreter in picking up and relaying incidental information and office politics.

Higher Education: Higher Expectations and More Complex Roles for Interpreters — From Deaf Eyes on Interpreting

This is the ninth weekly installment featuring highlights from the 20 chapters in the new book, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting, edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith, which is scheduled to be released in June by Gallaudet University Press.

As an attorney, Tawny Holmes shares her perspective on legal issues related to access for Deaf college students in her chapter, “Higher Education: Higher Expectations and More Complex Roles for Interpreters.” Her goal is to empower future Deaf college students to thoroughly understand their legal rights so that they may receive appropriate services to support their education.

She discusses ways that students can self-advocate regarding the interpreters they will use to access their education. For example, she comments that even though it is nice to have a “certified” interpreter, it is better to have one who is well-versed in the major area of study. She recounts her own experience in law school, where the interpreters were not familiar with the legal terminology used in her classes. So she had to spend extra time preparing the interpreters in terms of vocabulary and sign choice.

Providing ASL Interpreters in College Classes Does Not Ensure Equity —— From Deaf Eyes on Interpreting

This is the 4th weekly installment from the 20 chapters in the new book, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting, edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith, which is scheduled to be released in June by Gallaudet University Press. This chapter, American Sign Language Interpreting in a Mainstreamed College Setting: Performance Quality and Its Impact on Classroom Participation Equity, has three co-authors John Pirone, Jonathan Henner, and Wyatte C. Hall.

This is the 4th weekly installment from the 20 chapters in the new book, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting, edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith, which is scheduled to be released in June by Gallaudet University Press. This chapter, American Sign Language Interpreting in a Mainstreamed College Setting: Performance Quality and Its Impact on Classroom Participation Equity, has three co-authors John Pirone, Jonathan Henner, and Wyatte C. Hall.

As John Pirone describes in the video clip above, their research shows it is an illusion to think that providing an ASL interpreter in mainstreamed college classes provides equity for the Deaf students. He enumerates several areas of concern regarding interpreters’ skills and actions, including lack of ASL fluency, less than adequate ASL receptive skills, intercultural incompetency and lack of professionalism. In the full chapter, the co-authors propose solutions to this troubling state of affairs for Deaf students in interpreted college classrooms.

Visit Two Deaf-Owned Restaurants: Taipei’s Lotus and Bravo

Anna Mindess

As the waitress gently places the closed bud of a lotus flower in my pot of boiling broth, it slowly unfurls to show off its bright purple petals. CAN EAT? I sign to my new acquaintances around the table in this Deaf-owned restaurant. I see a chorus of nodding heads. It’s my first night in Taipei, but I’m already feeling quite at home thanks to the warm welcome from a half-dozen Deaf people and a couple of hearing interpreters who have come to dine with me at Lotus hot pot restaurant.

“Hot pot” refers to a classic Chinese DIY dinner, in which diners cook a variety of thinly sliced meats and a garden of vegetables in their own bubbling pots of broth. But Lotus hot pot is a bit different – and not just because its owner and many of the restaurant staff are Deaf – it also features an extra-healthy menu of organic vegetables, therapeutic broths with your choice of “Chinese medicine base” plus a salad bar of wild mountain herbs “to help remove toxins from the body.”

I look forward to meeting the owner of Lotus and learning his story, but right now, he’s busy in the kitchen. So, it’s time to eat. The server brings out platters of assorted cut-up veggies, sliced meats, fish balls, plus the shellfish I ordered. And here‘s my next challenge. After being an American Sign Language interpreter and hanging out with Deaf people for over 30 years, I am used to one of the consequences of a culture that values face-to-face communication above almost anything else: eating cold food. Sure, the food comes out of the kitchen hot. But since a bit of juicy news or a good story needs to be appreciated in its entirety, it would be impolite to interrupt signed remarks for something as basic as enjoying hot food. The food will still be there, albeit a little cooler, when the story is done.

In the case of a hot pot restaurant, however, each diner must cook the various ingredients in their broth and carefully remove them before they overcook, so that the vegetables don’t become mushy and the meat doesn’t toughen up. As a novice, I am attempting to juggle my chopsticks, the unfamiliar green botanicals and some slippery shellfish while simultaneously trying to converse with a tableful of guests who know varying amounts of ASL. The woman sitting next to me, Ginger Hsu, a hearing Taiwanese Sign Language interpreter who speaks some English, has been looking up on her phone the English words for unfamiliar ingredients. Once she notices that my timing is off and the vegetables in my pot are becoming limp, she volunteers to help cook my dinner while I chat away. What impressed me most during my two weeks in Taiwan was the caring kindness of strangers.

In the case of a hot pot restaurant, however, each diner must cook the various ingredients in their broth and carefully remove them before they overcook, so that the vegetables don’t become mushy and the meat doesn’t toughen up. As a novice, I am attempting to juggle my chopsticks, the unfamiliar green botanicals and some slippery shellfish while simultaneously trying to converse with a tableful of guests who know varying amounts of ASL. The woman sitting next to me, Ginger Hsu, a hearing Taiwanese Sign Language interpreter who speaks some English, has been looking up on her phone the English words for unfamiliar ingredients. Once she notices that my timing is off and the vegetables in my pot are becoming limp, she volunteers to help cook my dinner while I chat away. What impressed me most during my two weeks in Taiwan was the caring kindness of strangers.

Thanks to the global network of Deaf connections, this evening was organized for me by Will Chin, a thoughtful Taiwanese Deaf man who lived in the US for nine years while he attended Gallaudet, the University of Maryland and later taught.

The chain of Deaf acquaintances that led me to Will started with Melody Stein, who with her husband, runs San Francisco’s famous, Deaf-owned Mozzeria restaurant, which I wrote an article about on the eve of its opening in 2011. A couple of years later, when I was planning a trip to Hong Kong, I remembered that Melody was born there and asked if she had any friends in Hong Kong who might know ASL. She did and made the connection for me to the wonderful Jenny Lam, who had also attended Gallaudet. Jenny organized a dinner for me, much like this one, with a dozen Deaf people who had spent time in the US. Later, she took me an elegant dim sum restaurant because she knew I was writing an article about dim sum. When planning my trip to Taiwan, I contacted Jenny to see if she knew anyone in Taipei who might know ASL. She introduced me to Will Chin. When I emailed him and mentioned that besides being an ASL interpreter, I also write articles about food and culture for magazines and websites, Will knew I would love to visit this Deaf-owned restaurant.

After we finish eating, Will takes me back to the kitchen to meet owner Lu Chia-Hsun and interprets for me between Taiwanese Sign Language and ASL.

Lu previously had an office job, but in 2009, he worked on the International Deaflympics in Taipei. He had become ill because, he tells me, because he ate out a lot and didn’t make healthy choices. After mingling with Deaf athletes from around the world, he realized the importance of good food. When the Deaflympics ended, Lu looked for another job but became frustrated when he was repeatedly turned down. On his travels around Taiwan, he visited the city of Hualien and discovered a healthy hot pot restaurant, Sakura. He thought that opening a branch in Taipei would meet with success, asked his family to support him in this venture, and they agreed. But when Lu approached the owner of Sakura , he was met with resistance. Other people had tried to open branches of this restaurant but they had all failed. And now a deaf person with no restaurant experience! Lu’s family members negotiated on his behalf with the owner, saying if Lu fails, we will take responsibility. The owner finally agreed.

Lu opened the Taipei branch in 2009 and initially, not many customers came. Then slowly, as word spread about this healthy version of classical hot pot, the spot attracted more and more customers. “Business is very good now,” Lu tells me, “except when the weather is too hot. But when it’s cold outside, we have a huge line!”

Will Chin showed me Jiufen and two Deaf-owned restaurants

A few days later, after Will takes me to visit the quaint mountain town of Jiufen, we head back to Taipei for an afternoon coffee at Bravo, another Deaf-owned restaurant. This cozy café sports a sunshiny interior, from its butter yellow walls to its taxicab yellow coffee roaster and espresso machine. Since, like Lotus, this restaurant caters to both Deaf and hearing customers, the walls are decorated with illustrations of some crucial signs – especially for caffeine-deprived customers who need to get their morning fix in a hurry. While we wait for our drinks, I practice the signs for “Good morning, “Coffee,” and “Thank you.”

Johnny Lo makes coffee at Bravo

Will introduces me to husband and wife owners, Johnny Lo and Mandy Chang. Lo tells me that when he decided to open a coffee shop, he was warned that it was a very competitive business. In order to achieve coffee drinks with an exceptional taste, he studied privately with a teacher for a year and a half. And it took six months of practice, he adds, to master the flowers, swans and heart shapes he fashions out of foamed milk to top his coffee drinks.

His little shop attracts both Deaf and hearing customers. The busiest time is 8-10am for regular customers. Saturday is the most popular day for Deaf customers, who in Deaf cultural tradition, tend to stay all day. After their morning cups, they migrate outside to continue their conversations. On weekday afternoons, like today, there is usually a Deaf group around the table, who can sip and chat for hours. But if some new hearing customers come in, as I observe on this day, the Deaf regulars, quickly make space for them to be comfortable.

Lo and his wife, who are Bravo’s only employees, serve just coffee, cocoa and tea drinks plus waffles (in original, green tea and chocolate flavors). Since there are no hearing employees and Lo and his wife are both Deaf, they provide a large placard where customers can point to their drinks of choice.

As Will and I leave, I wiggle both thumbs to sign a big “Thank you” in Taiwanese Sign Language to Johnny and Mandy.

Deaf Interpreters: New Focus on a Traditional Role

As long as there have been Deaf people on earth, they have helped each other by explaining or interpreting to ensure that all members of the Deaf community have access to information. This often-overlooked facet of Deaf culture is currently receiving much well deserved attention in a variety of settings. In a new book, Deaf Interpreters at Work: International Insights, published by Gallaudet University Press, four distinguished editors and 17 contributors document the historical roots and current practices of Deaf interpreters in Australia, Canada, England, Finland, Ireland, Sweden and the United States .

While the professionalization of hearing people earning their living as sign language interpreters has eclipsed the traditional role played by Deaf people within their own society, there is currently a momentum for Deaf interpreters (DIs) to reclaim this traditional cultural role and work alongside hearing interpreters in the hospital, courtroom or on the conference stage.

In the Introduction to Deaf Interpreters at Work, the co-authors acknowledge that while DIs and hearing interpreters both follow a formalized code of conduct, there are crucial differences between them, including “the fact that DIs are Deaf all of the time…[consequently] DI and hearing interpreters have dissimilar access to information; DI and hearing interpreters have a different relationship with Deaf culture in that the former have more confidence in their position in that culture than do the latter.” The authors also describe a division of strengths: “DIs have a better understanding of sign language nuances, hearing interpreters have a better understanding of spoken language nuances…” (Adam et al. 2014, 7).

Deaf and Hearing Interpreters Can Work Together Effectively

In my own work specializing in legal interpreting for the past 20 years, I have had the privilege and pleasure to work with many highly skilled and creative CDIs (Certified Deaf Interpreters) in an array of challenging situations. I believe that this configuration can often achieve a deep accuracy not possible when hearing interpreters work alone.

For Deaf and hearing interpreters to work together successfully, however, they need training in a specific type of teamwork. Last week, I attended a three-day intensive conference in Denver which focused on Deaf and hearing interpreters working together effectively in the legal setting. The turnout at the ILI (Institute for Legal Interpreting) demonstrated a historical show of strength and a growing acknowledgement of the necessity for and power of Deaf interpreters. Of the 220 attendees, there were 54 CDIs from across the country. For more details see this post on Street Leverage.

Speaking of history, the attendees at ILI were treated to a fascinating presentation by Anne Leahy, a graduate student in Salt Lake City, who shared her historical research on Deaf interpreters being used in several court cases going back to the mid 1800’s. I look forward to Anne publishing these intriguing stories when her research is complete.

Recently, on the website Street Leverage, I issued a challenge to hearing interpreters to accept their pivotal position as “first responder.” When we are called to an interpreting assignment and must make the decision whether to halt the proceedings until a Deaf interpreter can be summoned, we truly hold the key to ensuring the most effective access to information for all parties involved. Here is a excerpt from my article:

Are Hearing Interpreters Responsible to Pave the Way for Deaf Interpreters?

Deaf interpreters are marching up the road to take their place as equal and valued professionals alongside their hearing counterparts. As more Deaf interpreters are trained, become certified and collaborate with hearing teammates, it will inevitably alter our way of working. We can welcome this evolving development and cherish the new opportunities it brings or dig in our heels and resist.

Two Street Leverage posts have addressed the gathering momentum of this movement. In Deaf Interpreters in the Blind Spot of the Sign Language Interpreting Profession, Jennifer Kaika documents the increasing numbers of Deaf interpreters and challenges us to support Deaf interpreters as “a long-standing and lasting part [of our profession], present since the inception of RID.” In Deaf Interpreters: The State of Inclusion, Nigel Howard, a Deaf interpreter himself, urges us to truly realize a team approach by “working together toward a shared and collaborative target language interpretation that is an equivalent to the source language.”

Recently, when revising my book, Reading Between the Signs, for a new edition, I added a section on Deaf interpreters. With the book’s focus on the cultural aspects of our work, it struck me that the resistance some hearing interpreters seem to feel to this “new” development in our field, might be rooted in cultural values (more about this later). First, let’s confirm the fact that Deaf interpreters belong to a tradition with deep roots.

LONG TRADITION

Eileen Forestal, a Deaf interpreter who has been at the forefront of research and training, contributed a chapter to the new book, Deaf Interpreters at Work: International Insights. While awarding official certificates to Deaf interpreters may be a relatively recent development, Forestal writes that, “as long as Deaf people have existed, they have been translating and interpreting within the Deaf community.” It goes back to the residential schools, where “Deaf children, both in and out of the classroom, would frequently explain, rephrase, or clarify for each other the signed communication used by hearing teachers.” Once out of school, this supportive activity did not cease. “Deaf persons would interpret for each other to ensure full understanding of information being communicated, whether in classrooms, meetings, appointments, or letters and other written documents” (Forestal, 2014, 30).

MY EXPERIENCE

Researching the history of Deaf interpreters allowed me to look back at my own career and see it through different eyes. After discovering the Deaf World via theater in the mid 1970’s when I was an actress in Los Angeles, I found CSUN where I took all four(!) classes offered at the time: ASL 1 and 2 and Interpreting 1 and 2.

Clearly, I was not prepared to work as a sign language interpreter, but with encouragement from my Deaf theater friends, I cautiously began community interpreting. In hindsight, I recall that at several Social Security or VR appointments, the Deaf person I was supposed to meet brought a “Deaf friend.” And if my interpretations were not clear enough, the friend would succinctly convey the point, assuming the role of unofficial “Deaf interpreter.”

In the mid-1980’s, I got a full time job at a large TDD distribution center in downtown Los Angeles to handle the crush of new customers thrilled to get the latest communication devices. When walk-in customers arrived, my co-worker, a Deaf woman named Sue Lee, would greet them and demonstrate their choice of equipment. My job was to interpret the registration process between Deaf customers and the hearing phone company reps on-site. As LA is a city of immigrants, it often happened that the Deaf person and I needed some extra help going over the rules of the program. I’d ask Sue to join us and she would come up with a way to best convey the information. Once again, everyone benefitted from the skills of a “Deaf interpreter,” although we didn’t label it as such at the time.

After moving to the San Francisco Bay Area, I continued community interpreting, but returned to CSUN in 1991 for a 6-week course in legal interpreting. Our class of two-dozen seasoned interpreters included 3 Deaf interpreters and we enjoyed figuring out how to best work together in the legal scenarios we practiced.

Over the last 20 years, I’ve specialized in legal interpreting and often team with Deaf interpreters (now CDIs). Most of my peak moments interpreting have occurred while collaborating with a Deaf interpreter to achieve the shared goal of optimal understanding. To me, it feels like dancing with the perfect partner. Having the benefit of teaming together repeatedly, we can often anticipate each other’s needs and intentions and seamlessly move as one.

For a new chapter in my book, I interviewed five very skilled Deaf interpreters with whom I have had the privilege and pleasure of working in court: Linda Bove, Daniel Langholtz, Priscilla Moyers, Ryan Shephard and Christopher Tester.

WHAT WE FOUND…

- To read the entire post go to: http://www.streetleverage.com/2014/08/are-hearing-interpreters-responsible-to-pave-the-way-for-deaf-interpreters/#sthash.FmpwyCpg.dpuf

“Article originally appeared on www.streetleverage.com. Reprinted with permission of Street Leverage.”

For more information on Deaf Interpreters check out the Deaf Interpreter Institute: http://www.diinstitute.org