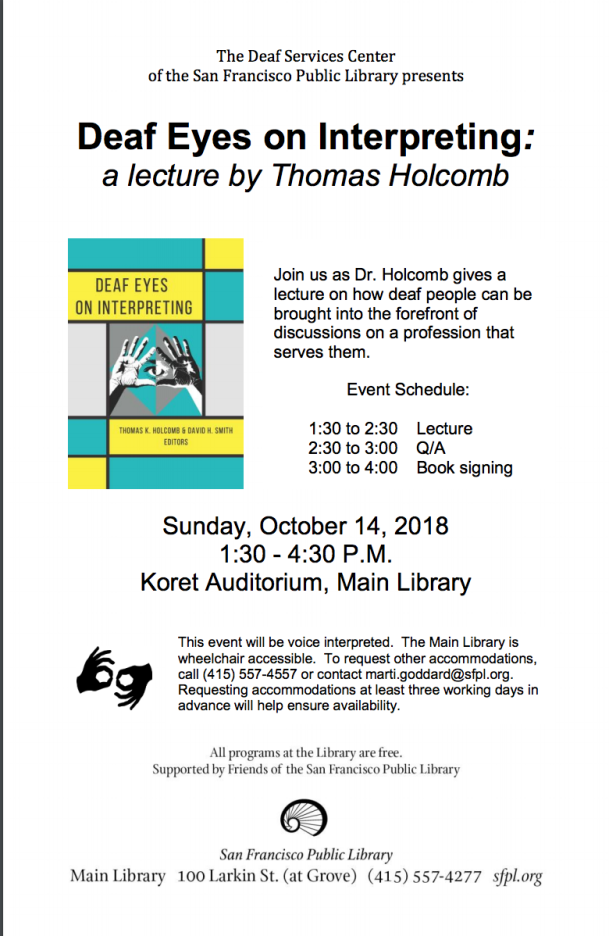

Join Tom Holcomb on Sunday, October 14th at the Main Branch of The San Francisco Public Library. He will be sharing his experiences preparing his latest book project, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting The discussion will include some of the issues that were covered in the book about ways the interpreting experience could be improved for both Deaf people and interpreters and is sure to be a lively event. See flyer below for details.

Tag Archives: Deaf Eyes on Interpreting

Tom Holcomb Lectures at San Francisco Main Library Sunday October 14, 1:30pm

YOUR NAME WHAT? YOU FROM WHERE?-Deaf Eyes on Interpreting

This is the twentieth weekly installment featuring highlights from the 20 chapters in the new book, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting, edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith, which was released in June by Gallaudet University Press.

Making connections is a critical aspect of Deaf culture. In this chapter, Naomi Sheneman states that if interpreters do not incorporate certain cultural conventions, like introducing themselves in a culturally appropriate manner before beginning their interpreting work, they send a message that they do not understand or respect Deaf culture. Consequently, Deaf people may have trouble trusting them. What is necessary is to specify their first name, last name, and the name of the agency that sent them. This is to make it easy for Deaf consumers to provide feedback.

Ignoring this custom perpetuates the conduit model and promotes a growing disconnect between the Deaf and interpreting communities. If interpreters cannot begin by introducing themselves properly, Deaf people would worry whether they are capable of facilitating cross-cultural communication. Sheneman calls on interpreter educators to educate future interpreters on ways to build a stronger connection with the Deaf community, including making culturally appropriate introductions.

Effectively Interpreting Content Areas Utilizing Academic ASL Strategies — Deaf Eyes on Interpreting

This is the nineteenth weekly installment featuring highlights from the 20 chapters in the new book, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting, edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith, which was released in June by Gallaudet University Press. In this chapter, co-authors, Chris Kurz, Kim Kurz and Raychelle Harris promote a Deaf-centered model of interpreting.

Currently, most deaf children are mainstreamed and receive their educational content through interpreters, not directly from teachers in their first language. The goal of this chapter is to help interpreters become more effective in presenting information in ways that Deaf children can really understand and learn academic material such as math, science, and history.

The co-authors’ work is based on empirical findings in brain research, academic ASL, and language acquisition. One example from the research has shown that the brain seeks patterns and relationships in order to compartmentalize knowledge, thus making it easier to recall at a later time. They urge interpreters to tap into valuable resources in the Deaf community, such as Deaf mathematicians and scientists who have grown up using ASL, as well as Certified Deaf Interpreters and learn from them how to best present complex information in ASL.

The Ingredients Necessary to Become a Favorite Interpreter — Deaf Eyes on Interpreting

This is the eighteenth weekly installment featuring highlights from the 20 chapters in the new book, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting, edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith, which was released in June by Gallaudet University Press.

Marika Kovacs-Houlihan draws a parallel between identifying ingredients needed to prepare a delicious meal and essential characteristics for an interpreter to become a favorite of Deaf people. She focuses on three critical ingredients: relationship, expertise, and humanity.

Expanding on these three ingredients, she adds that any good relationship requires active communication and dialogue, which takes time. Expertise she sees as a combination of life experience and academic training. Humanity is a matter of being honest and vulnerable. For example, the Deaf person needs to admit when they feel oppressed by the interpreter’s behavior. And the interpreter needs to acknowledge their hearing privilege.

She closes with a recommendation that ASL students need early exposure to the Deaf community in order to develop understanding and respect. She sees this best realized through service learning.

On Resolving Cultural Conflicts and the Meaning of Deaf-centered Interpreting — Deaf Eyes on Interpreting

This is the seventeenth weekly installment featuring highlights from the 20 chapters in the new book, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting, edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith, which was released in June by Gallaudet University Press.

This is the seventeenth weekly installment featuring highlights from the 20 chapters in the new book, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting, edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith, which was released in June by Gallaudet University Press.

Wyatte Hall makes the case that cultural conflicts are the basis of many of the problems between Deaf people and interpreters. While interpreters feel that they are following professional standards, Deaf people feel insulted that their cultural norms are being violated. For example, each group has a different perspective on the concept of “neutrality.” To Deaf people, neutrality means that an interpreter should work in a way that elevates the position of Deaf people to a level where they could truly function as equals to hearing people. But to most interpreters, neutrality means to treat both their Deaf and hearing consumers the same.

To improve the interpreting experience for Deaf people, Hall proposes that interpreting models need to evolve to a more on Deaf-centered approach. This model would address: feedback, pacing and partnership among other topics. His basic message is that interpreters should work WITH Deaf people, not FOR them.

Community Health Care Interpreting — Deaf Eyes on Interpreting

This is the sixteenth weekly installment featuring highlights from the 20 chapters in the new book, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting, edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith which was released in June by Gallaudet University Press.

This is the sixteenth weekly installment featuring highlights from the 20 chapters in the new book, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting, edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith which was released in June by Gallaudet University Press.

Perhaps the most critical area, where it is vitally important that an interpreter’s skills match the Deaf consumer’s needs, is in the health care field. This chapter, “Community Health Care Interpreting,” was co-written by Cynthia Plue, Lewis Lummer, Susan Gonzales, and Marta Ordaz.

As described by Plue in the video above, attention must be paid to four key competency areas in order to meet the diverse needs of various segments of the evolving Deaf community. These include competency and clarity in communication, language proficiency, cultural competency, and healthcare literacy. Especially important is the ability to meet the needs of Deaf individuals with limited language and/or educational backgrounds, as well as those who are Deaf blind. For these individuals, the authors encourage the use of certified Deaf interpreters to ensure successful delivery of critical healthcare information. Another solution Plue suggests is the use of a chart to outline the communication, language, literacy needs and preferences of each Deaf patient to minimize a potentially life-threatening mismatch.

It Takes Two to Tango: Crafting a Flawless Partnership in the Corporate World — From Deaf Eyes on Interpreting

This is the fifteenth weekly installment featuring highlights from the 20 chapters in the new book, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting, edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith which was released in June by Gallaudet University Press.

This is the fifteenth weekly installment featuring highlights from the 20 chapters in the new book, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting, edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith which was released in June by Gallaudet University Press.

Sam Sepah holds a prominent position at Google as a Global Program Manager. He discusses the partnership between the increasing numbers of Deaf professionals, administrators and managers and their Designated Interpreters. Sepah draws a distinction between freelance interpreters who may randomly be assigned by an agency and “designated interpreters” who routinely work with the same Deaf clients 20-40 hours a week.

The title of this chapter, “It Takes Two to Tango,” reflects the author’s conviction that in order to create an effective partnership in the corporate culture, both the Deaf professional and the interpreter need to share their expectations, agree on communication strategies, provide each other with feedback, do their research and practice their moves, so they can work together as seamlessly as two dance partners.

Hey Listen, Mainstreamed Deaf Children Deserve More! – From Deaf Eyes on Interpreting

This is the fourteenth weekly installment featuring highlights from the 20 chapters in the new book, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting, edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith which was released in June by Gallaudet University Press.

This is the fourteenth weekly installment featuring highlights from the 20 chapters in the new book, Deaf Eyes on Interpreting, edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith which was released in June by Gallaudet University Press.

Fallon Brizendine is a Deaf professional working to educate future interpreters. She expands on concerns raised by Amy June Rowley in our last blog post regarding placing novice interpreters in the pivotal role of working with Deaf children in mainstreamed schools. Whether they like it or not, without a critical mass of Deaf language models in their lives, the Deaf students will look to their interpreters as language models. This places a heavy responsibility on them.

However, Brizendine has some concrete ideas to remedy this situation. She suggests that interpreters be ready to take on this important role by visiting bilingual ASL/English classrooms and observing the bilingual teachers to see the manner in which they deliver lessons and interact with their students in ASL. She also puts responsibility on Deaf professionals who work in the educational field, such as herself, to connect with educational interpreters and offer them feedback and support.

Educational Interpreting from Deaf Eyes — from Deaf Eyes on Interpreting

This is the thirteenth weekly installment featuring highlights from the 20 chapters in the new book,Deaf Eyes on Interpreting edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith which was released in June by Gallaudet University Press.

This is the thirteenth weekly installment featuring highlights from the 20 chapters in the new book,Deaf Eyes on Interpreting edited by Thomas K. Holcomb and David H. Smith which was released in June by Gallaudet University Press.

In her chapter, Amy June Rowley explains why she refuses to subject her own Deaf children to interpreter-mediated education, based on her own personal experiences growing up in mainstreamed programs. In addition, she cites studies showing how Deaf students are being serviced by poorly qualified interpreters in many mainstreamed programs.

Rowley emphasizes several points: young Deaf students in mainstreamed settings are often isolated without full access to language, culture and social opportunities. Interpreters may be the only persons with knowledge of Deaf culture and ASL, yet many interpreters do not have a clear understanding of the scope of their roles. In fact, Interpreter Training Programs often put their students in educational settings as internships, giving the message that this is an appropriate place in which to start their careers. Rowley disagrees and sees it as a place for experienced interpreters with many years of experience.

She recommends interpreters partner with members of the Deaf Community and educators of Deaf children to give Deaf children the best, most supported start.